| I plan to evaluate the potential of video games to foster engagement and improved performance on assessments (particularly of higher-order thinking skills) among secondary school students and to determine what software exists, is in development, or could be developed that would facilitate the use of gaming to that end. I plan to evaluate the potential of computer-based games to foster engagement and improved performance on assessments, particularly of higher-order thinking skills, among secondary school students and to determine what software exists, is in development, or could be developed that would facilitate the use of gaming to that end. This problem seems to lend itself to a quantitative design. Questions can be divided into quasi-experimental and non-experimental categories. I. Quasi-Experimental Questions: These questions are best answered through an experimental design, but true experimental groups cannot be easily assigned in the school setting intended for this study. A. Do students demonstrate more engagement (on-task behavior) when learning activities are game-based? (Difference Question: This is an observable behavior that can be monitored and documented during game-based and more traditional lessons.) B. Do students taught through game-based learning experiences outperform those taught through more traditional instructional methods? (Difference Question: Assessments of experimental and control groups’ performances can be compared .) II. Non-Experimental: Some of my questions could be answered by either experimental or non-experimental study. Others are best addressed through survey. A. Ex Post Facto: Past studies may help to answer these questions: 1. Do students demonstrate more engagement (on-task behavior) when learning activities are game-based? (Difference Question) 2. Do students taught through game-based learning experiences outperform those taught through more traditional instructional methods? (Difference Question) B. Survey: 1. What are students’ feelings about, perceptions of, gaming in the classroom? (Descriptive Research Question) 2. What are teachers’ feelings about, perceptions of and anticipated problems with implementing gaming in the classroom? (Descriptive Research Question) I am finding that this problem is pretty complex. In any experimental approach, there will be many variables to account for. As I conduct research, I hope to find that some of my questions are addressed adequately in the literature, so that I might narrow the focus of my study. One question that I expect might be answered almost entirely through a review of related literature and similar investigation (How would I categorize a search on Amazon, eBay, or at Best Buy? Would such investigations inform my review of related literature?) is: What software exists, is in development, or could be developed to facilitate student engagement and performance? I also need to research assessment designs that can measure higher-order thinking skills such as application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Again, I hope that I can narrow the scope of my problem through my investigation of related literature, in order to focus on a single question in the final design. I am now beginning to question whether I will be able to find any educational game software that focuses on the higher-order thinking skills that interest me. Computers are not truly thinking machines, so most computer learning software is rote focused. I hope I am not painting myself into a corner with this topic. I can envision a game that would fit this bill, but there are few that I know of, none of which fit into the "educational" genre. This begs the question, would students using entertainment game software for learning demonstrate greater motivation and performance on higher-order thinking assessments than peers taught an equivalent lesson without gaming software? Although many entertainment video games may lack intellectually challenging content, and others may contain content that is inappropriate for a school setting, there are others (For example: strategy games, construction games, simulations) that may have great merit as teaching tools. I am very interested in any insights and advice anyone may have, particularly regarding focusing my topic. |

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Video Gaming for Higher Order Thinking

Sunday, March 14, 2010

Playing to Learn

In Behaviorism in Practice , I mentioned a game called Typing of the Dead. I love to play games, and believe we have only begun to tap their potential as learning and productivity tools. So I have decided my research focus should be on gaming to learn.

| Born in 1969, I witnessed the evolution of the personal computer. When I was a child, a computer was, at least in my imagination, a room full of beeping steel cabinets studded with flashing lights and slowly spinning reels of magnetic tape, tended by white coated scientists in sterile and secure government facilities as it performed mathematical calculations. I remember the introduction of TRS-80s in school, and the first home game consoles. These machines promised a new era for education, but what fascinated me at the time were the new games that allowed you to “play the TV.” I remember the appearance of Pong (computer table tennis) at the arcade and on joysticked home consoles, and the accelerating evolution from 8 bit graphics (See the circle eat the dot!) to today’s immersive “virtual reality” gaming environments. For the most part, my parents and their generation considered these games a complete waste of time, even an abuse of the powerful technology that made them possible. But others felt that computer gaming could be a valuable learning medium. When I became a teacher, one of the first things I “splurged” on with my new “adult” salary was a Playstation game console with a copy of the hit game Tomb Raider. At that time, the new 3-D environment seemed so vast and immersive that I feared I would get lost, so I fell back on my travel experience and bought a guidebook with walkthroughs for every level of the game. Reading and playing, I worked my way through the game, dedicating unconscionable hours of study and repeated effort to meet every challenge and explore every corner of that magical digital world. That year, a few days after I finished the game, I discovered that I had a student in detention for some recurring behavior problem that I cannot now recall. He was amiable enough, for a student in detention, and we ended up talking about video games. He, too, was playing Tomb Raider, but he was stuck at some puzzle about a third of the way through the game. I gave him a tip to help him get past it and, when he asked me how I had figured that out, told him I was using the game guide. We ended up establishing a contract stipulating that I would lend him my game guide if he would extinguish his undesirable behavior. He ended up doing fairly well in my literature class, and even better in the game, and he thanked me for both—especially the loan of the game guide which, he confessed, he had relied on heavily. And that made me think. These game walkthroughs, especially in those early days, were filled with fairly complex technical writing. And mine, being cheap, had little in the way of illustrations. It occurred to me that my student had demonstrated diligence, reading comprehension, and application of what he had read in completing the game. If he had applied these abilities to his studies, I thought, he could easily have earned an “A.” I wondered if it would be possible to design learning games, focused on our curricular goals, which would be as appealing and sophisticated as Tomb Raider. Unfortunately, as computer games had evolved greatly, learning games failed to compete in quality with games designed purely for entertainment. Of course, there were plenty of education games on the market, but most were poorly designed, with low production value and correspondingly low appeal. Even the best games seemed to do little to encourage the higher-order application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation skills that I seek to foster in my students (Paul, 1985). As a high school teacher, I wanted to see games that dealt with the literature and thinking skills that are the foci of our system’s curriculum. Over the years I have seen evidence of progress in the development of learning games. I have also seen an increase in the relevance and perceived legitimacy of computer gaming in mainstream culture and business. I am convinced that play is not only compatible with learning, but that the primary purpose of play is learning. I use games as instruction and assessment tools in my classroom and often find that students are more engaged and enthusiastic about learning experiences when they are packaged as play. Still, I find that game software specifically designed for learning is less appealing than that which is designed strictly for entertainment, and that learning games tend to focus on mechanical skills, simple calculation, and rote memorization of isolated facts. But just as television in the 1970s was only beginning to realize its potential as an instructional medium, I believe that computer gaming has yet to reveal its value as a learning resource. I hope to investigate the potential of games to facilitate active learning among secondary school students, particularly regarding these higher order thinking skills, and what software exists, is in development, or could be developed that would facilitate the use of gaming to that end. I believe that this problem is amenable to research based on the “Guiding Principles of Scientific, Evidence-Based Inquiry” proposed by McMillan & Schumacher (2008, p. 7). This issue is significant because it could inform the development and implementation of curriculum and classroom lessons. Students may be more motivated to engage in learning experiences presented as games. Research on this issue can be linked to relevant educational theories as well. Many of the effective learning games, and recreational video games, have employed behaviorist techniques, but I believe computer games have the potential to support implementation of a wide range of learning theories, including constructivism, constructionism, connectivism, and social learning theory (Beaumie, 2001; Davis, Edmunds, & Kelly-Bateman, 2001; Palmer, Peters, & Streetman, 2007; Pitler, Hubbell, Kuhn, & Malenoski, 2007). This is particularly true in relation to creative and simulation games, but any game genre has the potential to create a context in which learners can construct meaning, individually or socially. A cursory review of search terms related to my topic has revealed that others have conducted research in this field, but the ever-changing nature of technology recommends ongoing study. I believe that this research problem lends itself to the systematic data collection and logical analysis that defines research. The results will be interesting to teachers looking for ways to increase student engagement and motivation, and may well offer a vision of a major aspect of the future of educational practice. References Beaumie, K. (2001). Social constructivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved November 27, 2009, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/ Davis, C., Edmunds, E., & Kelly-Bateman, V. (2001). Connectivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved November 27, 2009, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/ McMillan, J. H., & Schumacher, S. (2008). Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry (Laureate custom edition). Boston: Pearson. Palmer, G. Peters, R., & Streetman, R. (2001). Cooperative learning. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved November 27, 2009, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/ Paul, R. W. (1985). Bloom's Taxonomy and critical thinking instruction. Educational Leadership, 42(8), 36-40. Pitler, H., Hubbell, E., Kuhn, M., & Malenoski, K. (2007). Using technology with classroom instruction that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. |

Monday, December 21, 2009

Reflections on My Personal Learning Theory in Light of Bridging Learning Theory, Instruction, and Technology

At the beginning of the Bridging Learning Theory, Instruction, and Technology course, I characterized my personal theory of learning as “a synthesis of theories supported by research and my own experience both as a teacher and as a learner.” Throughout this course, my understanding of learning theory, pedagogy, and the technologies available for their implementation has grown, and this growth is reflected in my approach to facilitating student learning in the classroom.

This course has reinforced my belief in the wisdom of learner-centered pedagogy. Behaviorist, cognitivist, constructivist, constructionist, and social constructionist learning theory remain foundations of my own teaching philosophy, and these theories support my understanding that lasting and relevant learning occurs when the student is actively involved in building meaning (Laureate Education, Inc., 2009; Lever-Duffy & McDonald, 2008). This course has added to my understanding of this principle by developing my knowledge of how technology can support pedagogical approaches that reflect modern, student-centered, learning theories.

Our second week in this course focused on behaviorism. Like many thinkers in education, I had begun to consider behaviorism less relevant in modern education than more cognition-centered learning theories. But revisiting behaviorist learning theory through our course readings reminded me of its lasting significance and applicability in concert with other learning theories in modern schooling (Pitler, Hubbell, Kuhn, & Malenoski, 2007; Smith, 1999). Like all worthy theories of learning, behaviorism addresses the importance of relevance in learner motivation.

Our third week focused on cognitive learning theory which, unlike behaviorism, attempts to explain the processes through which new information is incorporated by learners into their existing understanding of the world (Novak & Cañas, 2008). Through our readings, I gained a greater understanding of how cognitive learning theory can be applied in the classroom, adding to my repertoire of technologies that support strategies such as cues, questions, advance organizers, summary, and note taking. Although I have employed these strategies throughout my teaching career, I gained a greater understanding of why they work and what resources have recently become available for their application. We learned how several technology tools can support cognitive learning in practice. Some—like concept mapping, Word features, presentation tools, and online communication and collaboration tools—I immediately applied and will continue to use in student-centered learning contexts.

In week four we explored constructivist and constructionist learning theory, which suggests that meaningful learning occurs when learners construct meaning for themselves through active experience (Laureate Education, Inc., 2009). For me, this is the most exciting of the learning theories we have investigated, and offers the most promise for changing the way I teach. As an English teacher, I have always engaged my students in constructivist and constructionist learning experiences. Traditional reading and writing assignments reflect these principles, as learners must construct meaning for themselves in transactions with the text and other readers, and writers must develop understanding of their topics as they construct written artifacts of their thinking. New media, however, offer me the opportunity to employ constructivist and constructionist learning theory in exciting new ways. Students can use computer and Internet technologies to engage in authentic problem-based and project-based learning experiences that make new learning relevant and immediately applicable in authentic contexts to aid in motivation and retention (Pitler et al., 2007). Already, I am applying these ideas in class projects where students are building their own understanding, not only of new content, but of how to learn and apply new knowledge independently and collaboratively to solve real-world problems and create valuable resources. My AP Language and Composition students are currently building a wiki-based study guide for the AP test and SAT vocabulary presentations they will use to prepare their peers for college entrance examinations and coursework. Their study guide and its development incorporate many skills, technologies and tools besides the host wiki, including summary, organizers, concept maps, tables, illustrative images, and rubrics. The skills my students develop for learning and applying content knowledge will be at least as important to them as the content knowledge itself.

Week five of this course introduced connectivism and social learning, examining how people learn with and from others. From the connectivist perspective, students in social learning situations apply their diverse perspectives, experience, and prior knowledge to actively construct meaning, creating connections to interpret seemingly unrelated events and ideas (Davis, Edmunds, & Kelly-Bateman, 2001). Cooperative learning, in particular, is an effective instructional strategy that reflects social learning theories by enabling students to work together to actively construct knowledge and transform it in ways that aid comprehension for group members (Palmer, Peters, & Streetman, 2007; Pitler et al., 2007). I am particularly excited by the potential of Web 2.0 collaboration and social networking tools to aid and enhance cooperative learning by helping groups of students work collaboratively with individual accountability to construct and share group products. My greater understanding of how to structure and manage cooperative learning experiences for my students, and technologies to serve that effort, will certainly be reflected in my classroom practice.

In week six, we focused on synergizing learning theories, strategies, and technologies (Laureate Education, Inc., 2009; Muniandy, Mohammad, & Fong, 2007). We examined nine proven categories of learning strategy (identifying similarities and differences, summarizing, providing recognition and reinforcement of effort, assigning meaningful homework and practice, using nonlinguistic representation, facilitating cooperative learning, setting clear objectives and providing feedback, generating and testing hypotheses, and providing cues and advance organizers) and found ways to apply them to realize learning theory in our classroom practice (Laureate Education, Inc., 2001). I found that I already apply many of these strategies in my teaching, but also found that I can improve my exploitation of those strategies I already use while developing my repertoire of pedagogical techniques in other areas.

In the long term, I hope to more consciously connect learning theory to pedagogical practice, and to use technology more as a learning tool rather than for instruction. The lesson I developed in week seven reflects a synthesis of much of what I learned throughout this course. This lesson reflects both the immediate adjustments I have made to my instructional practice, like the use of Web 2.0 collaboration tools to facilitate cooperative learning, and long-term changes I will make regarding the integration of technology into my practice. I have already incorporated new learning technologies, like wikis, Google Docs, and concept mapping software, into my daily instruction. I have also developed new ways of using technologies I once used mainly for instruction (such as PowerPoint) as learning tools, by putting them in the hands of students. As my students build their animated PowerPoint “movie” versions of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, I will step away from the front of the classroom to take on a more powerful role as facilitator for a social constructionist learning experience. This lesson is just one example of many to come that will combine cognitivist, constructivist, constructionist, and social learning theories with classroom strategies and supportive technologies to provide my students with meaningful, learner-centered, active learning experiences through which they will develop the skills they will need to adapt to the constant technological change that will define their careers.

In the future, I intend to continue to adapt new technologies to facilitate the application of learning theory and best pedagogical practices to student learning. There are many technologies I hope to employ in applying best pedagogical practices and learning theory, but I am particularly interested in making the most of new presentation tools, such as interactive whiteboards, and Web 2.0 collaboration and publication tools for social constructivist and constructionist learning. Our school has recently received four interactive whiteboards. Already, teachers are preparing lessons to use them for instruction. I am thinking of ways they can be used in a more learner-centered context. As a result of pressure and persuasion on the part of teachers in my system who have been frustrated with impediments to using Web 2.0 technologies in the classroom, our technology department has announced a plan to certify teachers, through an online course, to override the school’s prohibitive Internet filter at their own discretion. I intend to take this course and make the most of the long overdue privileges this certification will confer. With access to image search engines, wikis, weblogs, and the endless variety of Web-based learning tools this will make available, my students will enjoy much greater opportunities to take control of their own education through authentic, meaningful learning experiences. It will be wonderful to have more of these tools at my disposal, but I must remember to always employ them in the execution of proven pedagogical strategies based on sound learning theory.

References

Davis, C., Edmunds, E., & Kelly-Bateman, V. (2001). Connectivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved November 27, 2009, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/

Laureate Education, Inc. (Executive Producer). (2009). Bridging learning theory, instruction, and technology. Baltimore: Author.

Lever-Duffy, J. and McDonald, J. (2008). Theoretical Foundations. In Teaching and Learning with Technology (3rd ed. pp. 2–35 ). Boston: Pearson.

Muniandy, B., Mohammad, R., & Fong, S. (2007, September). Synergizing pedagogy, learning theory and technology in instruction: How can it be done?. US-China Education Review, 4(9), 46–53. Retrieved from Education Research Complete database. Document ID: 31626898

Novak, J. D. & Cañas, A. J. (2008). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them, Technical Report IHMC CmapTools 2006-01 Rev 01-2008. Retrieved from the Institute for Human and Machine Cognition Web site: http://cmap.ihmc.us/Publications/ResearchPapers/TheoryUnderlyingConceptMaps.pdf

Pitler, H., Hubbell, E., Kuhn, M., & Malenoski, K. (2007). Using technology with classroom instruction that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Smith, M. K. (1999) The behaviourist orientation to learning. The Encyclopedia of Informal Education, Retrieved November 11, 2009, from www.infed.org/biblio/learning-behavourist.htm

This course has reinforced my belief in the wisdom of learner-centered pedagogy. Behaviorist, cognitivist, constructivist, constructionist, and social constructionist learning theory remain foundations of my own teaching philosophy, and these theories support my understanding that lasting and relevant learning occurs when the student is actively involved in building meaning (Laureate Education, Inc., 2009; Lever-Duffy & McDonald, 2008). This course has added to my understanding of this principle by developing my knowledge of how technology can support pedagogical approaches that reflect modern, student-centered, learning theories.

Our second week in this course focused on behaviorism. Like many thinkers in education, I had begun to consider behaviorism less relevant in modern education than more cognition-centered learning theories. But revisiting behaviorist learning theory through our course readings reminded me of its lasting significance and applicability in concert with other learning theories in modern schooling (Pitler, Hubbell, Kuhn, & Malenoski, 2007; Smith, 1999). Like all worthy theories of learning, behaviorism addresses the importance of relevance in learner motivation.

Our third week focused on cognitive learning theory which, unlike behaviorism, attempts to explain the processes through which new information is incorporated by learners into their existing understanding of the world (Novak & Cañas, 2008). Through our readings, I gained a greater understanding of how cognitive learning theory can be applied in the classroom, adding to my repertoire of technologies that support strategies such as cues, questions, advance organizers, summary, and note taking. Although I have employed these strategies throughout my teaching career, I gained a greater understanding of why they work and what resources have recently become available for their application. We learned how several technology tools can support cognitive learning in practice. Some—like concept mapping, Word features, presentation tools, and online communication and collaboration tools—I immediately applied and will continue to use in student-centered learning contexts.

In week four we explored constructivist and constructionist learning theory, which suggests that meaningful learning occurs when learners construct meaning for themselves through active experience (Laureate Education, Inc., 2009). For me, this is the most exciting of the learning theories we have investigated, and offers the most promise for changing the way I teach. As an English teacher, I have always engaged my students in constructivist and constructionist learning experiences. Traditional reading and writing assignments reflect these principles, as learners must construct meaning for themselves in transactions with the text and other readers, and writers must develop understanding of their topics as they construct written artifacts of their thinking. New media, however, offer me the opportunity to employ constructivist and constructionist learning theory in exciting new ways. Students can use computer and Internet technologies to engage in authentic problem-based and project-based learning experiences that make new learning relevant and immediately applicable in authentic contexts to aid in motivation and retention (Pitler et al., 2007). Already, I am applying these ideas in class projects where students are building their own understanding, not only of new content, but of how to learn and apply new knowledge independently and collaboratively to solve real-world problems and create valuable resources. My AP Language and Composition students are currently building a wiki-based study guide for the AP test and SAT vocabulary presentations they will use to prepare their peers for college entrance examinations and coursework. Their study guide and its development incorporate many skills, technologies and tools besides the host wiki, including summary, organizers, concept maps, tables, illustrative images, and rubrics. The skills my students develop for learning and applying content knowledge will be at least as important to them as the content knowledge itself.

Week five of this course introduced connectivism and social learning, examining how people learn with and from others. From the connectivist perspective, students in social learning situations apply their diverse perspectives, experience, and prior knowledge to actively construct meaning, creating connections to interpret seemingly unrelated events and ideas (Davis, Edmunds, & Kelly-Bateman, 2001). Cooperative learning, in particular, is an effective instructional strategy that reflects social learning theories by enabling students to work together to actively construct knowledge and transform it in ways that aid comprehension for group members (Palmer, Peters, & Streetman, 2007; Pitler et al., 2007). I am particularly excited by the potential of Web 2.0 collaboration and social networking tools to aid and enhance cooperative learning by helping groups of students work collaboratively with individual accountability to construct and share group products. My greater understanding of how to structure and manage cooperative learning experiences for my students, and technologies to serve that effort, will certainly be reflected in my classroom practice.

In week six, we focused on synergizing learning theories, strategies, and technologies (Laureate Education, Inc., 2009; Muniandy, Mohammad, & Fong, 2007). We examined nine proven categories of learning strategy (identifying similarities and differences, summarizing, providing recognition and reinforcement of effort, assigning meaningful homework and practice, using nonlinguistic representation, facilitating cooperative learning, setting clear objectives and providing feedback, generating and testing hypotheses, and providing cues and advance organizers) and found ways to apply them to realize learning theory in our classroom practice (Laureate Education, Inc., 2001). I found that I already apply many of these strategies in my teaching, but also found that I can improve my exploitation of those strategies I already use while developing my repertoire of pedagogical techniques in other areas.

In the long term, I hope to more consciously connect learning theory to pedagogical practice, and to use technology more as a learning tool rather than for instruction. The lesson I developed in week seven reflects a synthesis of much of what I learned throughout this course. This lesson reflects both the immediate adjustments I have made to my instructional practice, like the use of Web 2.0 collaboration tools to facilitate cooperative learning, and long-term changes I will make regarding the integration of technology into my practice. I have already incorporated new learning technologies, like wikis, Google Docs, and concept mapping software, into my daily instruction. I have also developed new ways of using technologies I once used mainly for instruction (such as PowerPoint) as learning tools, by putting them in the hands of students. As my students build their animated PowerPoint “movie” versions of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, I will step away from the front of the classroom to take on a more powerful role as facilitator for a social constructionist learning experience. This lesson is just one example of many to come that will combine cognitivist, constructivist, constructionist, and social learning theories with classroom strategies and supportive technologies to provide my students with meaningful, learner-centered, active learning experiences through which they will develop the skills they will need to adapt to the constant technological change that will define their careers.

In the future, I intend to continue to adapt new technologies to facilitate the application of learning theory and best pedagogical practices to student learning. There are many technologies I hope to employ in applying best pedagogical practices and learning theory, but I am particularly interested in making the most of new presentation tools, such as interactive whiteboards, and Web 2.0 collaboration and publication tools for social constructivist and constructionist learning. Our school has recently received four interactive whiteboards. Already, teachers are preparing lessons to use them for instruction. I am thinking of ways they can be used in a more learner-centered context. As a result of pressure and persuasion on the part of teachers in my system who have been frustrated with impediments to using Web 2.0 technologies in the classroom, our technology department has announced a plan to certify teachers, through an online course, to override the school’s prohibitive Internet filter at their own discretion. I intend to take this course and make the most of the long overdue privileges this certification will confer. With access to image search engines, wikis, weblogs, and the endless variety of Web-based learning tools this will make available, my students will enjoy much greater opportunities to take control of their own education through authentic, meaningful learning experiences. It will be wonderful to have more of these tools at my disposal, but I must remember to always employ them in the execution of proven pedagogical strategies based on sound learning theory.

References

Davis, C., Edmunds, E., & Kelly-Bateman, V. (2001). Connectivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved November 27, 2009, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/

Laureate Education, Inc. (Executive Producer). (2009). Bridging learning theory, instruction, and technology. Baltimore: Author.

Lever-Duffy, J. and McDonald, J. (2008). Theoretical Foundations. In Teaching and Learning with Technology (3rd ed. pp. 2–35 ). Boston: Pearson.

Muniandy, B., Mohammad, R., & Fong, S. (2007, September). Synergizing pedagogy, learning theory and technology in instruction: How can it be done?. US-China Education Review, 4(9), 46–53. Retrieved from Education Research Complete database. Document ID: 31626898

Novak, J. D. & Cañas, A. J. (2008). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them, Technical Report IHMC CmapTools 2006-01 Rev 01-2008. Retrieved from the Institute for Human and Machine Cognition Web site: http://cmap.ihmc.us/Publications/ResearchPapers/TheoryUnderlyingConceptMaps.pdf

Pitler, H., Hubbell, E., Kuhn, M., & Malenoski, K. (2007). Using technology with classroom instruction that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Smith, M. K. (1999) The behaviourist orientation to learning. The Encyclopedia of Informal Education, Retrieved November 11, 2009, from www.infed.org/biblio/learning-behavourist.htm

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

A VoiceThread on Impediments to Using Digital Learning Technology in Our School

Follow this link: http://voicethread.com/share/777235/

This is a VoiceThread about impediments to using Web based and computer learning tools in my school. It talks about the Bess "SMARTFILTER" Internet filter, the lack of access to computers, our inability to install learning software on the computers without administrative privileges (which nobody in the building has), and the general lack of faith in teachers' ability to make pedagogical decisions regarding the Internet. This is a work in progress, as is our school system's technology policy. No doubt, both will evolve over time.

This is a VoiceThread about impediments to using Web based and computer learning tools in my school. It talks about the Bess "SMARTFILTER" Internet filter, the lack of access to computers, our inability to install learning software on the computers without administrative privileges (which nobody in the building has), and the general lack of faith in teachers' ability to make pedagogical decisions regarding the Internet. This is a work in progress, as is our school system's technology policy. No doubt, both will evolve over time.

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

Connectivism and Social Learning in Practice

Social learning can take many forms, but the essence of social learning theory is the idea that people learn with and from others (Laureate, 2001). From the connectivist perspective of Davis, Edmunds, and Kelly-Bateman (2001), students in social learning situations bring the flexibility enabled by their diverse experience to bear in social learning situations where they combine and share prior knowledge, experience, perceptions, and comprehension to actively construct meaning by creating connections and interpreting seemingly unrelated events and ideas. Cooperative learning is an instructional strategy that reflects social learning theories by enabling students to work together to actively construct knowledge and transform it in ways that aid comprehension for group members (Pitler, Hubbell, Kuhn, & Malenoski, 2007; Palmer, Peters, & Streetman, 2007). The ability to work collaboratively with peers to build knowledge needed to accomplish a shared task will be the essential career skill of this century (Davis, Edmunds, & Kelly-Bateman, 2001; Leavy & Murnane, 2006). Web 2.0 social networking and collaboration tools can facilitate and enhance the effectiveness of cooperative learning by providing media in which groups of students can work collaboratively and with individual accountability to create and share group products.

Collaborative learning can be used to apply social learning theory by aiding students in constructing their own understanding of the world. According to Kim Beaumie’s (2001) interpretation of social constructivist learning theory, reality is “constructed through human activity” in a process through which people “invent the properties of the world” together (p. 1). In this model of learning, human knowledge is actively socially constructed and reflects the shared understandings, interests, and assumptions of groups. Beaumie (2001) recommends that formal learning experiences include reciprocal teaching, peer collaboration, cognitive apprenticeship, problem-based instruction, webquests, anchored instruction, and other activities designed to support the shared construction of knowledge.

These strategies can be supported by Web 2.0 and other digital communication and presentation tools. Students can construct presentations using PowerPoint, concept mapping, VoiceThread, or other computer and Internet applications to support reciprocal teaching. Collaboration tools such as wikis and Google Docs can aid student groups in collaboratively developing meaningful artifacts of their learning. One particularly helpful feature of these applications is that they keep records of the history of site or document development and contributors’ asynchronous discussions in order to ensure the individual accountability required by cooperative learning strategy (Palmer, Peters, & Streetman, 2007). Social networking tools like MySpace and Facebook also provide a medium for both social interaction and artifact construction, as does the rich virtual environment of Second Life. These digital collaboration and communication tools can also help to convert what Jean Lave described as inert knowledge, knowledge that is not immediately applied by the learner and is unlikely to be applied in future experience, into active knowledge that is, and can be, put to use (Laureate, 2009). Students can consult with experts and community members in fields they are studying through weblogs, email, and chat applications to support a cognitive apprenticeship model or to help answer questions in a problem-based instruction task. Problem-based and collaborative instruction can also be supported through the ready availability of online research tools such as search engines, online libraries, and databases.

As the Web closes the distance that once separated individuals and communities, it offers greater potential for the realization of meaningful and diverse application of social learning theory. But the shrinking or “flattening” of the world through digital information and communication technology also increases the importance of developing in our students the skill of self-directed learning (Davis, et al., 2001; Laureate, 2009; Pitler, et al., 2007). These tools help students collaboratively convert the unprecedented abundance of information now available into useful knowledge that can be practically applied to make sense of the present and make predictions and prescriptions for the future (Davis, et al., 2001; Laureate, 2009). In an increasingly competitive, and cooperative, world, these are more than just classroom strategies; they are long-term survival skills.

References

Beaumie, K. (2001). Social constructivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved November 27, 2009, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/

Davis, C., Edmunds, E., & Kelly-Bateman, V. (2001). Connectivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved November 27, 2009, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/

Laureate Education, Inc. (Executive Producer). (2009). Bridging learning theory, instruction, and technology. Baltimore: Author.

Levy, F., & Murnane, R. (2006). Why the changing American economy calls for twenty-first century learning: Answers to educators' questions. New Directions for Youth Development, 2006(110), 53–62.

Palmer, G. Peters, R., & Streetman, R. Cooperative learning. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved November 27, 2009, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/

Pitler, H., Hubbell, E., Kuhn, M., & Malenoski, K. (2007). Using technology with classroom instruction that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Constructivism in Practice

Constructivist and constructionist learning theories are rooted in the principle that real learning occurs when learners actively construct meaning for themselves through active experience (Laureate, 2009). Constructionist learning theory suggests that this experience should result in the building of an external artifact (Laureate, 2009; Han & Bhattacharya, 2001). Although the validity of these theories has long been accepted, practical impediments have traditionally interfered with their widespread implementation. Now, digital information, communication, and collaboration tools are facilitating teachers’ ability to realize these principles in classroom instruction.

There are many ways to use computer technology to implement constructivist and constructionist learning theory in practice. Dr. Michael Orey suggests that PowerPoint can be used to create the final artifact of a project-based, constructivist lesson (Laureate, 2001). Students are given a challenging topic to address in their presentation and encounter, through their preparation, situations that create disequilibration, a state that occurs when existing schemata do not account for unexpected situations or new information. Students must then either assimilate new information into an existing schema, or create a new schema to accommodate it. Either way, because they immediately apply new knowledge or skills to the completion of a meaningful task, they are more likely to be fully engaged in the learning experience and to retain new knowledge and skills. This process is fundamental to all constructionist learning situations.

In Emerging Perspectives on Learning, Teaching, and Technology, Han and Bhattacharya (2001) describe a workshop on effective Web-based instruction in which the facilitator uses a constructionist learning model. She begins by eliciting background information about participants and their goals for the workshop. She previews activities and opens the floor for questions, asks for ideas about the topic to tap participants’ prior knowledge (which she records on a flip-chart), highlights common themes and significant points in their responses, and integrates them into a PowerPoint presentation representing the collective knowledge of the group. The then presents the PowerPoint to the group with illustrating anecdotes before introducing participants to Web-based instruction examples. When they have examined these models, she records the group’s reflections on their experiences, which they share in a whole-group debriefing. With these experiences, participants individually construct their own Web-based instruction with lists of required components to guide them. These components are learner analysis, timeframe, interface metaphor, multiple presentation modes, assessment strategies, a variety of learning tasks, and a learner centered environment. They then form groups that discuss and select plans for presentation. Presentations are followed by comments and questions from the audience and reflective discussion. The workshop is followed by ongoing online communication through participant facilitated chat sessions. Final individual projects are shared and critiqued online. This process illustrates constructionist learning theory by holding to the principle that “instruction is only effective when the learners can relate personally and take something away from it” (Han & Bhattacharya, 2001, p.2). It moves through planning, implementing, and processing phases with active participant involvement at every stage. The activity is learner-oriented, interactive, based on understanding of learners and their contexts, centers on construction of an artifact, and uses multiple presentation methods (Han & Bhattacharya, 2001).

Ideally, a constructionist learning environment uses rubrics to establish expectations, discussion of and interpretation of assignment parameters, exploration of multiple strategies for the assignment, inquiry and learning during development, presentation of work, revision and development of the idea in the project, learner collaboration, collaboration with experts, and authentic tasks to provide a meaningful context (Han & Bhattacharya, 2001). A good example of problem-based instruction that reflects these standards is the Nikron example Glazer (2001) describes, in which a group of students collaborate with stakeholders in their community in an attempt to determine whether pollution from an important local industry is responsible for recent fish kills. Students are given a personally relevant, real world problem, they formulate research questions, assign questions to groups, evaluate available information resources, devise various forms of final products to present their findings, propose and negotiate projects with their teacher and media specialist, devise methods for research, conduct research, experiment, observe, share and compare research with other teams, analyze evidence, surmise the cause of the kill, return to the hypothesis and develop a presentation, present for whole-class review, and finish with a mock trial as a final assessment of their efforts and findings. This illustrates Glazer's (2001) assertion that “learning is most meaningful and is enhanced when students face a situation in which the concept is immediately applied” (p. 2). Answers to the question come from the learners’ knowledge and experience, rather than from texts or curricula, and the learning community is an integral part of the mechanism of knowledge construction.

Glazer (2001) also suggests other types of problem-based learning projects, such as anchored instruction, in which the problem comes from a learning context such as a story, adventure, or other situation with a problem that students can resolve through inquiry. He recommends online resources such as Web quests and an online desert race simulation. In Web quests, the design includes a task or problem, a process description, resources, evaluation tools, and concluding summary and debriefing.

In Using Technology with Classroom Instruction that Works, Pitler, Hubbell, Kuhn, & Malenoski (2007) discuss technology enhanced activities in which students are called upon to generate and test hypotheses. In one activity, students are given a sum of money to invest. They use spreadsheet software to predict how various investment strategies will turn out over the course of thirty years. In other examples, students use probeware to examine the relationship between light and color in art, or to determine if the students’ community has acid rain. He also examines an online video game developed by a teacher that helps students discover the causes of World War II through a simulation. In each case, students are actively involved in solving a real problem or constructing an authentic product in a personally significant context.

Many online resources support and describe constructivist and constructionist learning. Edutopia: Project Learning offers several examples of project-based learning experiences. In “Immersing Students in Civic Education,” Richard Rapaport (2007) describes a project in which a class of students was called upon to propose tile designs for a real renovation project for the San Francisco Port Commission. A valuable part of their learning experience was rejection by their evaluator, urban designer Dan Hodapp. This feedback, although painful, drove home the reality of the project and communicated higher expectations than would be expected in ordinary school projects. Students revised their designs to reflect a more focused theme and eventually won approval. This first step led to the difficult discovery process of learning how to actually produce the tiles. Despite many episodes of discomfort, disequilibration, and struggle in their zones of proximal development, the team ultimately prevailed. Now every student on that team can see and show an authentic artifact of their learning experience at the city’s renovated Pier 14.

Apple Learning Interchange offers several examples of online project-based learning activities (Apple, Inc., 2008). In “March of the Monarchs,” students track the northerly migration of monarch butterflies in a project entitled Journey North, funded by the Annenberg/CPB project. Students in states visited annually by the butterflies create a digital map marking sightings to document their migration. In this complex, interdisciplinary collaborative project, student groups measure the growth of plants on which the butterflies feed, calculate the growth time of larvae, analyze weather conditions that affect the migration, observe interrelated species, explore cultural references to monarchs, study other states they pass through, explore and document their life-cycle, take and post photographs, and explore every conceivable aspect of this insect’s life. While they become experts on the monarch, they also develop expertise in many other learning disciplines, all while working collaboratively to address a locally relevant, real-world issue and create an authentic product for a wide audience.

Another interesting project on Apple Learning Interchange is the International Education and Resource Network's (iEARN) First People's Project, which involves indigenous students around the world in creating and sharing artifacts of their local cultures with the global community (Apple, Inc., 2008). Students present stories, interviews, digital photographs, poems, and artwork representing their indigenous cultures, often creating the only widely available information sources on their communities’ ways of life. They share packages with other indigenous participants around the world, providing the genuinely valuable service of preserving and sharing their cultural traditions while developing their own skills and understanding of their heritage.

Problem-based, project-based, and inquiry-based learning experiences put constructivist and constructionist learning theories into practice in ways that engage students and produce cognitive and concrete results, and digital information, communication, and collaboration tools have made these projects more accessible and practical than ever before. Making use of these opportunities, teachers can help their students develop the confidence and abilities they will need to compete, and triumph, in the twenty-first century global marketplace.

REFERENCES

Apple, Inc. (2008). Online project-based learning. Apple learning interchange. Retrieved November 24, 2009, from http://edcommunity.apple.com/ali/story.php?itemID=598&version=341&page=2

Glazer, E. (2001). Problem based instruction. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/

Han, S., and Bhattacharya, K. (2001). Constructionism, Learning by Design, and Project Based Learning. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/

Laureate Education, Inc. (Executive Producer). (2009). Bridging learning theory, instruction, and technology. Baltimore: Author.

Lever-Duffy, J. and McDonald, J. (2008). Theoretical Foundations. In Teaching and Learning with Technology (3rd ed. pp. 2–35 ). Boston: Pearson.

Pitler, H., Hubbell, E., Kuhn, M., & Malenoski, K. (2007). Using technology with classroom instruction that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Rapaport, R. (2007). Immersing students in civic education. Edutopia. Retrieved November 24, 2009, from http://www.edutopia.org/intelligent-design

There are many ways to use computer technology to implement constructivist and constructionist learning theory in practice. Dr. Michael Orey suggests that PowerPoint can be used to create the final artifact of a project-based, constructivist lesson (Laureate, 2001). Students are given a challenging topic to address in their presentation and encounter, through their preparation, situations that create disequilibration, a state that occurs when existing schemata do not account for unexpected situations or new information. Students must then either assimilate new information into an existing schema, or create a new schema to accommodate it. Either way, because they immediately apply new knowledge or skills to the completion of a meaningful task, they are more likely to be fully engaged in the learning experience and to retain new knowledge and skills. This process is fundamental to all constructionist learning situations.

In Emerging Perspectives on Learning, Teaching, and Technology, Han and Bhattacharya (2001) describe a workshop on effective Web-based instruction in which the facilitator uses a constructionist learning model. She begins by eliciting background information about participants and their goals for the workshop. She previews activities and opens the floor for questions, asks for ideas about the topic to tap participants’ prior knowledge (which she records on a flip-chart), highlights common themes and significant points in their responses, and integrates them into a PowerPoint presentation representing the collective knowledge of the group. The then presents the PowerPoint to the group with illustrating anecdotes before introducing participants to Web-based instruction examples. When they have examined these models, she records the group’s reflections on their experiences, which they share in a whole-group debriefing. With these experiences, participants individually construct their own Web-based instruction with lists of required components to guide them. These components are learner analysis, timeframe, interface metaphor, multiple presentation modes, assessment strategies, a variety of learning tasks, and a learner centered environment. They then form groups that discuss and select plans for presentation. Presentations are followed by comments and questions from the audience and reflective discussion. The workshop is followed by ongoing online communication through participant facilitated chat sessions. Final individual projects are shared and critiqued online. This process illustrates constructionist learning theory by holding to the principle that “instruction is only effective when the learners can relate personally and take something away from it” (Han & Bhattacharya, 2001, p.2). It moves through planning, implementing, and processing phases with active participant involvement at every stage. The activity is learner-oriented, interactive, based on understanding of learners and their contexts, centers on construction of an artifact, and uses multiple presentation methods (Han & Bhattacharya, 2001).

Ideally, a constructionist learning environment uses rubrics to establish expectations, discussion of and interpretation of assignment parameters, exploration of multiple strategies for the assignment, inquiry and learning during development, presentation of work, revision and development of the idea in the project, learner collaboration, collaboration with experts, and authentic tasks to provide a meaningful context (Han & Bhattacharya, 2001). A good example of problem-based instruction that reflects these standards is the Nikron example Glazer (2001) describes, in which a group of students collaborate with stakeholders in their community in an attempt to determine whether pollution from an important local industry is responsible for recent fish kills. Students are given a personally relevant, real world problem, they formulate research questions, assign questions to groups, evaluate available information resources, devise various forms of final products to present their findings, propose and negotiate projects with their teacher and media specialist, devise methods for research, conduct research, experiment, observe, share and compare research with other teams, analyze evidence, surmise the cause of the kill, return to the hypothesis and develop a presentation, present for whole-class review, and finish with a mock trial as a final assessment of their efforts and findings. This illustrates Glazer's (2001) assertion that “learning is most meaningful and is enhanced when students face a situation in which the concept is immediately applied” (p. 2). Answers to the question come from the learners’ knowledge and experience, rather than from texts or curricula, and the learning community is an integral part of the mechanism of knowledge construction.

Glazer (2001) also suggests other types of problem-based learning projects, such as anchored instruction, in which the problem comes from a learning context such as a story, adventure, or other situation with a problem that students can resolve through inquiry. He recommends online resources such as Web quests and an online desert race simulation. In Web quests, the design includes a task or problem, a process description, resources, evaluation tools, and concluding summary and debriefing.

In Using Technology with Classroom Instruction that Works, Pitler, Hubbell, Kuhn, & Malenoski (2007) discuss technology enhanced activities in which students are called upon to generate and test hypotheses. In one activity, students are given a sum of money to invest. They use spreadsheet software to predict how various investment strategies will turn out over the course of thirty years. In other examples, students use probeware to examine the relationship between light and color in art, or to determine if the students’ community has acid rain. He also examines an online video game developed by a teacher that helps students discover the causes of World War II through a simulation. In each case, students are actively involved in solving a real problem or constructing an authentic product in a personally significant context.

Many online resources support and describe constructivist and constructionist learning. Edutopia: Project Learning offers several examples of project-based learning experiences. In “Immersing Students in Civic Education,” Richard Rapaport (2007) describes a project in which a class of students was called upon to propose tile designs for a real renovation project for the San Francisco Port Commission. A valuable part of their learning experience was rejection by their evaluator, urban designer Dan Hodapp. This feedback, although painful, drove home the reality of the project and communicated higher expectations than would be expected in ordinary school projects. Students revised their designs to reflect a more focused theme and eventually won approval. This first step led to the difficult discovery process of learning how to actually produce the tiles. Despite many episodes of discomfort, disequilibration, and struggle in their zones of proximal development, the team ultimately prevailed. Now every student on that team can see and show an authentic artifact of their learning experience at the city’s renovated Pier 14.

Apple Learning Interchange offers several examples of online project-based learning activities (Apple, Inc., 2008). In “March of the Monarchs,” students track the northerly migration of monarch butterflies in a project entitled Journey North, funded by the Annenberg/CPB project. Students in states visited annually by the butterflies create a digital map marking sightings to document their migration. In this complex, interdisciplinary collaborative project, student groups measure the growth of plants on which the butterflies feed, calculate the growth time of larvae, analyze weather conditions that affect the migration, observe interrelated species, explore cultural references to monarchs, study other states they pass through, explore and document their life-cycle, take and post photographs, and explore every conceivable aspect of this insect’s life. While they become experts on the monarch, they also develop expertise in many other learning disciplines, all while working collaboratively to address a locally relevant, real-world issue and create an authentic product for a wide audience.

Another interesting project on Apple Learning Interchange is the International Education and Resource Network's (iEARN) First People's Project, which involves indigenous students around the world in creating and sharing artifacts of their local cultures with the global community (Apple, Inc., 2008). Students present stories, interviews, digital photographs, poems, and artwork representing their indigenous cultures, often creating the only widely available information sources on their communities’ ways of life. They share packages with other indigenous participants around the world, providing the genuinely valuable service of preserving and sharing their cultural traditions while developing their own skills and understanding of their heritage.

Problem-based, project-based, and inquiry-based learning experiences put constructivist and constructionist learning theories into practice in ways that engage students and produce cognitive and concrete results, and digital information, communication, and collaboration tools have made these projects more accessible and practical than ever before. Making use of these opportunities, teachers can help their students develop the confidence and abilities they will need to compete, and triumph, in the twenty-first century global marketplace.

REFERENCES

Apple, Inc. (2008). Online project-based learning. Apple learning interchange. Retrieved November 24, 2009, from http://edcommunity.apple.com/ali/story.php?itemID=598&version=341&page=2

Glazer, E. (2001). Problem based instruction. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved

Han, S., and Bhattacharya, K. (2001). Constructionism, Learning by Design, and Project Based Learning. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved

Laureate Education, Inc. (Executive Producer). (2009). Bridging learning theory, instruction, and technology. Baltimore: Author.

Lever-Duffy, J. and McDonald, J. (2008). Theoretical Foundations. In Teaching and Learning with Technology (3rd ed. pp. 2–35 ). Boston: Pearson.

Pitler, H., Hubbell, E., Kuhn, M., & Malenoski, K. (2007). Using technology with classroom instruction that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Rapaport, R. (2007). Immersing students in civic education. Edutopia. Retrieved November 24, 2009, from http://www.edutopia.org/intelligent-design

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Cognitivism in Practice

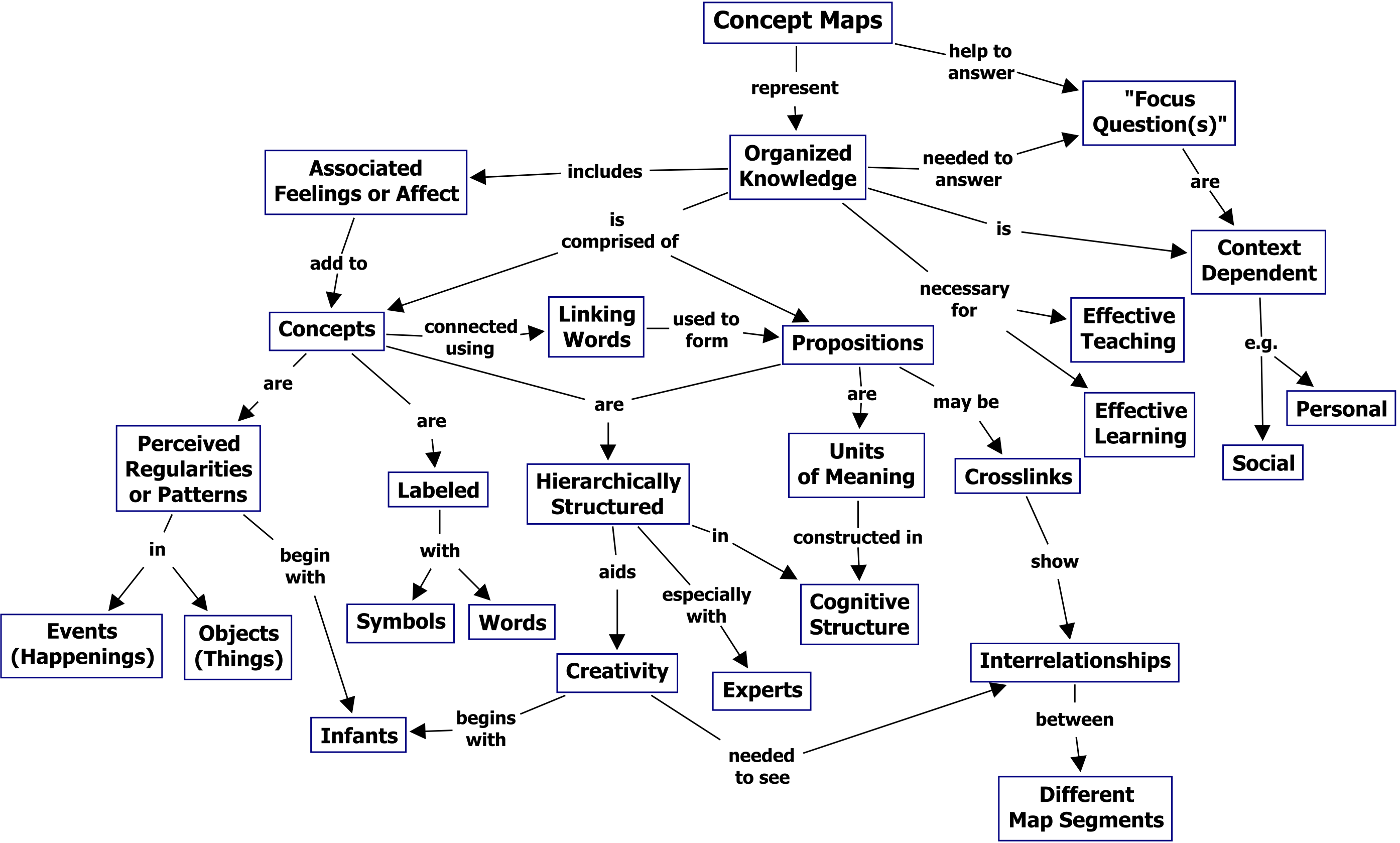

Chapter four of Pitler et al.’s (2007) book, “Cues, Questions, and Advance Organizers” examines strategies that help learners “retrieve, use, and organize information about a topic” (p. 73). Cues and questions offer reminders that help students recall prior knowledge in order to prepare them to connect that prior knowledge to new information in an imminent learning experience. This strategy employs Ausubel et al.’s notion that authentic learning occurs when new ideas are assimilated into the learner’s existing cognitive structure (Novak & Cañas, 2008). According to Pitler et al. (2007), Ausubel developed advance organizers to help students organize and comprehend new information, particularly when it is presented in a poorly organized context. These organizers can take many forms (expository organizers, narrative organizers, graphic organizers, cues, inferential questions, analytic questions, questions and organizers produced by skimming ahead), as long as they provide some structure to guide subsequent ordering and interpretation of content (Pitler et al., 2007). Different types of organizers are appropriate for different purposes and may reflect different learning styles or intelligences, but all should be designed to focus on important content. Organizers produce more meaningful understanding if they focus on higher-order cognitive processes—those on the upper levels of Bloom’s taxonomy such as application, analysis, evaluation, and creation—rather than lower-level thinking such as factual recall (Pitler et al., 2007). Spreadsheets, concept maps, KWL charts, and even pre-reading background development through media experiences such as film clips and virtual field trips can provide advance scaffolding for learning experiences. Concept mapping tools such as CmapTools and Inspiration are particularly well suited to help students connect prior knowledge to existing cognitive structures because of their visual representation of connections among ideas. Learners may begin constructing a concept map by recording prior knowledge about a topic and showing how ideas are interrelated, then expand the map during and after the new learning experience. This application of constructivist learning theory can be further augmented when learners work collaboratively, either locally or through the Internet. Working collaboratively, learners may augment peers’ learning experiences by providing timely assistance when in what Vygotsky called the zone of proximal development (Novak & Cañas, 2008). As learners apply newly acquired information from their short term memory to the task of constructing the concept map, it moves into their working memory and, through the experience of visually representing interrelationships among ideas, becomes connected to prior knowledge and permanently established in long-term memory (Novak & Cañas, 2008). Multimedia tools can be used in similar ways to represent relationships between prior knowledge and new information in ways that appeal to various learning styles and intelligences. Use of images in multimedia organizers, presentations, and virtual field trips using computer technology takes advantage of the benefits of combining text and images Allen Paivio referred to as dual coding (Laureate, 2009). Students can use these technologies to incorporate new information into artifacts that represent episodic, archaic, or iconic associations (Novak & Cañas, 2008). And many of the same technologies that facilitate advance organization of new information are applicable to summarizing and note-taking.

(Novak &Cañas, 2008)

Pitler et al. (2007) define summary and notetaking skills as the “ability to synthesize information and distill it into a concise new form” (p. 119). Learners summarize by eliminating extraneous and redundant data, replacing lists of specifics with set categories, and finding or generating topic sentences (Pitler et al., 2007). Computers can facilitate this process through word processing, concept mapping, presentation, information retrieval, communication, and collaboration applications. Microsoft Word is a particularly versatile tool. Students can use the auto summarize feature to condense content produced by others (perhaps to compare with their own summaries) or to check their own writing to see if their meaning is evident. Word can also be used for brainstorming, through its bullet feature, or to produce advance organizers representing various organizational frames using drawing or table generating tools. Concept mapping programs can be used to assimilate new ideas, but maps can also be exported in outline form to facilitate summarization and presentation of organized notes. Presentation tools, like PowerPoint, are a great medium for producing and sharing combination notes, especially for their capacity to integrate a variety of media (Pitler et al., 2007). Small groups collaborating on such a project may divide responsibilities for this production based on individual intelligences and learning preferences. Easy access to information, images, narratives, audio, and video resources through Internet search engines and databases can help students focus on developing and incorporating, rather than searching for, content. Communication and collaboration tools, such as blogs and wikis, allow learners to engage in reciprocal teaching, or share and collaboratively build learning artifacts based on their summaries and notes on shared learning experiences (Pitler et al., 2007).

Although the application of computer technology does not, in itself, guarantee effective learning, information and communication technologies can be used to implement cognitive learning theories to facilitate meaningful student learning.

References

Laureate Education, Inc. (Executive Producer). (2009). Bridging learning theory, instruction, and technology. Baltimore: Author.

Novak, J. D. & Cañas, A. J. (2008). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them, Technical Report IHMC CmapTools 2006-01 Rev 01-2008. Retrieved from the Institute for Human and Machine Cognition Web site: http://cmap.ihmc.us/Publications/ResearchPapers/TheoryUnderlyingConceptMaps.pdf

Pitler, H., Hubbell, E., Kuhn, M., & Malenoski, K. (2007). Using technology with classroom instruction that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Behaviorism in Practice

Although behaviorist learning theory may be unfashionable in a time when constructivism, learning styles, and multiple intelligences share the spotlight, behaviorism remains a staple of learning practice in and out of the classroom. The recognition that one cannot live on bread alone does not, after all, imply that bread should be removed from one’s diet entirely. Behaviorism, appropriately applied, is an indispensable part of educational practice because students learn when effective learning behavior is reinforced. Certain technologies can support effective operant conditioning to reinforce student effort, homework, and practice (Pitler, Hubbell, Kuhn, & Malenoski, 2007).

Most teachers know that students often fail to recognize the connection between effort and performance. I have frequently heard students attributing bad grades to their teachers' personal opinions of them. Only when pressed, might they admit that the reason their teachers didn’t like them was their lack of effort in class. This faulty perception of cause and effect is often deep-seated, even comforting, as it excuses the student from taking responsibility for failure. But this misconception can be remedied, if the student is confronted with undeniable evidence of the true cause and effect relationship between effort and performance. Pitler, Hubbell, Kuhn, and Malenoski (2007) recommend that students use rubrics and spreadsheet software to document their efforts in class. A rubric describing levels of effort in different categories allows students to quantify their behaviors so that they may be recorded on a spreadsheet. Students can then record their performance on assessments and use the software’s graphing functions to compare their effort with their performance. This method can be effective in many curricular areas and in interdisciplinary projects. Pitler et al. argue that through “consistent and systematic exposure to teaching strategies like this one” students can “really grasp the impact that effort can have on their achievement” (p. 159). They also recommend that students use data collection tools to examine statistical evidence of this correlation on a larger scale, so that they can generalize their understanding beyond a particular classroom situation. By allowing students to clearly see the consequences of their efforts, such a system reinforces behaviors that contribute to learning and academic success.

Homework and practice are also important learning behaviors that are often undervalued by students. Again, the positive consequences of effort expended on homework and practice can be so remote that they are not immediately evident to learners. Some educational technologies, including “word processing applications, spreadsheet applications, multimedia, web resources, and communication software,” can provide the sort of programmed instruction that makes effective use of behaviorist learning theory (Laureate Education, Inc., 2009; Pitler et al., 2007, p. 189). For example, Pilter et al. (2009) point out that Microsoft Word offers students immediate feedback on their writing, amounting to a reward for students who are keeping score, with a Flesch-Kincaid grade level rating feature, and can assist them with immediately improving their “score” by offering a thesaurus feature (p. 190). This is perfectly in keeping with Skinner’s programmed instruction model (Laureate, 2009; Smith, 1999).

Pilter, et al. (2009) also describe constructivist learning projects, such as PowerPoint games, that provide immediate intrinsic rewards for their creators’ and users’ success at applying curricular knowledge and skills. Here we see that there can be synergy, rather than conflict, between behaviorism and other learning theories.

The authors recommend a number of sites that provide behaviorism-based and other learning applications:

• EDDIE Awards: www.computedgazette.com/page3.html

• BESSIE Awards: www.computedgazette.com/page11.html

• Technology & Learning’s Awards of Excellence/Readers’ Choice Awards: http://www.technlearning.com/

• eSchoolNews Readers’ Choice Awards: www.eschoolnews.com/resources/surveys/editorial/rca/

• CodIE Awards: www.siia.net/codies

• Discovery Education’s The Parent Channel: http://school.discovery.com/parents/reviewcorner/software/

• BattleGraph: http://sarah.lodick.com/edit/powerpoint_game/battlegraph/battlegraph.ppt

• BBC Skillswise: www.bbc.co.uk/skillswise

• National Library of Virtual Manipulatives: http://nlvm.usu.edu/en/nav/vlibrary.html

• ExploreLearning: http://www.explorelearning.com/

• BrainPOP: http://www.brainpop.com/

• IKnowthat.com: http://www.iknowthat.com/

• Wizards & Pigs: www.cogcon.org/gamegoo/games/wiznpigs/wiznpigs.html

• Flashcard Exchange: http://www.flashcardexchange.com/

• Mousercise: www.3street.org/mouse

• Lever Tutorial: www.elizrosshubbell.com/levertutorial

• Kitchen Chemistry: http://pbskids.org/zoom/games/kitchenchemistry/virtual-start.html

• Hurricane Strike!: http://meted.ucar.edu/hurrican/strike/index.htm

• Stellarium: http://www.stellarium.org/

• Instant Projects: http://instantprojects.org/ (Pitler, et al., 2007, pp. 193- 198)

REFERENCES

Laureate Education, Inc. (Executive Producer). (2009). Bridging learning theory, instruction, and technology. Baltimore: Author.

Pitler, H., Hubbell, E., Kuhn, M., & Malenoski, K. (2007). Using technology with classroom instruction that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Smith, M. K. (1999) The behaviourist orientation to learning. The Encyclopedia of Informal Education, Retrieved November 11, 2009, from www.infed.org/biblio/learning-behavourist.htm

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Reflections on Understanding the Impact of Technology on Education, Work, and Society

Over the past thirteen years, I have attended hundreds of professional development sessions and courses. Unfortunately, few have had practical significance in my daily teaching. When I hopefully signed up for educational technology courses, I inevitably ended up receiving primers on PowerPoint, Google search, and other applications with which I was already well versed. While I occasionally learned useful shortcuts or interesting uses for familiar programs, I seldom learned anything that would radically change my teaching. Because of its focus on Web 2.0 applications and connecting tools, practice, and theory, taking the Understanding the Impact of Technology on Education, Work, and Society course has been exceptional.

Before this course began, I primarily used digital information and communication technology for planning, presentation, and research. I used daily PowerPoints to combine diverse media into appealing, smoothly flowing presentations, reducing down-time in the classroom. I used interactive hypertext and audio versions of literature to augment in-class reading. Still, this could be classified as doing the same old things—posting text on the board, playing recorded texts, showing films and still images, recording class notes—in a new way (Thornburg, 2004). I found ways to use the computer linked LCD projector and PowerPoint to do different things, but the technologies I was using were more appropriate for teacher-centered instruction and had limited potential to facilitate the sort of project-based, student-centered, constructivist learning that best prepares students for the twenty-first century workplace (Laureate, 2008).